Well…Here I am. Finally at the end of my career as a student. Forever and always. Of course, I’ll never stop learning. But as far as formal education goes, stick a fork in me, I’m done. That is, if you don’t count the massive pile of homework I have to somehow manage to finish up in the next week and a half (and who’s counting that, right?).

With that said, this week I’m taking some time to reflect on my time in the Public History New Media course this semester. Us public historians looooove that thing called reflective practice.

At the beginning of the semester I wasn’t really sure what to expect. On the one hand, I’ve been using a lot of the media that this course addressed for many years; but on the other, technology tends to hate me. A lot. So I just wasn’t sure how it was going to turn out. Spoiler alert: It turned out fine, and I even learned some things in the process.

I learned HTML! (See what I did there?) When I was much younger and much less cool, I was so jealous of those people who had really fancy backgrounds and layouts and fonts. But I couldn’t for the life of me figure out how they did it! Turns out they could probably code (or knew someone who could). Now my Myspace can be cool, too, because I know how to code. I also conquered iMovie and PhotoShop, and honed my Twitter and Omeka skills.

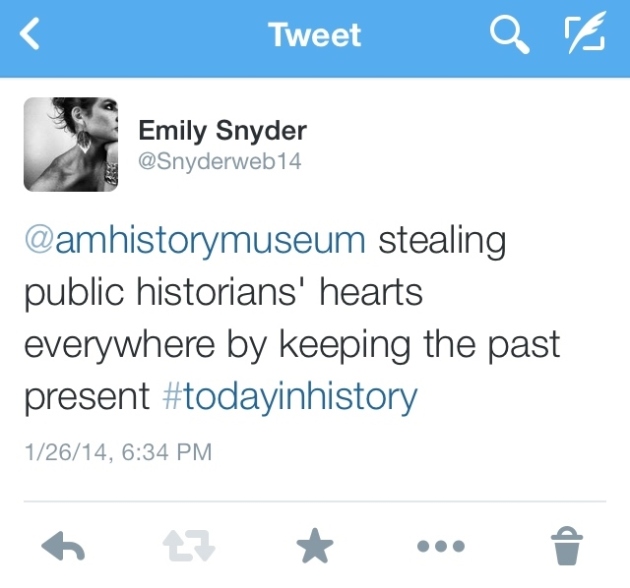

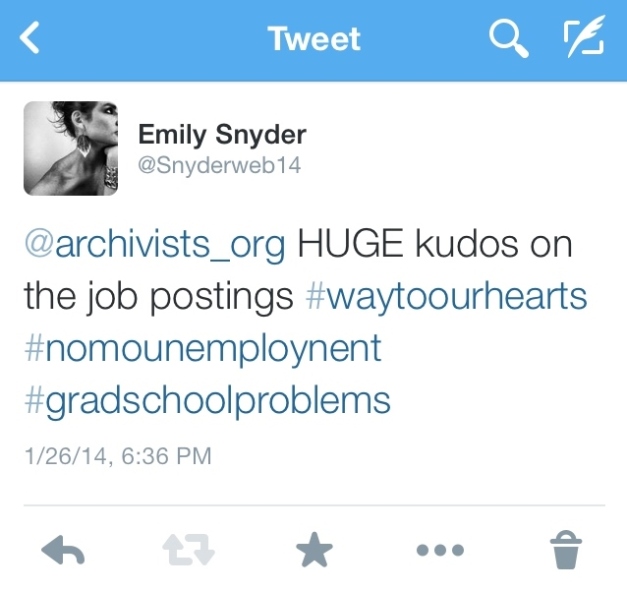

Now…”How does this all fit in with Public History?” you ask. More than most people might think, actually. As people are pelted more and more every day with digital technologies, it is of crucial importance that public history institutions adapt and use these to their advantage. Today, it would be nearly impossible to find a museum or archives that didn’t have a website. Many even have online collections and exhibitions. Institutions are moving away from print advertisements in newspapers and magazines, and focusing more heavily on digital campaigns that are grounded in social media sites such as Twitter and Facebook. Even inside the institutions themselves one cannot escape the digital. Many museums are incorporating digital elements into their exhibitions, such as QR codes, computer interactives, and specified hashtags. I knew all of this coming into this class because, as a member of the so-called “digital native” category, none of this is new to me. I am used to going to museums and seeing these things. What I didn’t think as much about, however, is that a large portion of audiences are not used to this.

The most important thing I learned in this class is that using digital media in the public history sphere is important, but it’s even more important to use it consciously. Just because we can doesn’t always mean we should. And when we do choose to use digital media to advertise, tell a story, or to create/enhance an experience, we must make sure we are considering all factors that will influence the outcome, particularly audience expectation and access. After this class, I now feel confident that I can go out into the world and use digital media effectively in my public history endeavors.

Now I just need to get to that final mountain of homework…

See you on the other side!!